THE NEW EAGLE CREEK SALOON (2019-ONGOING)

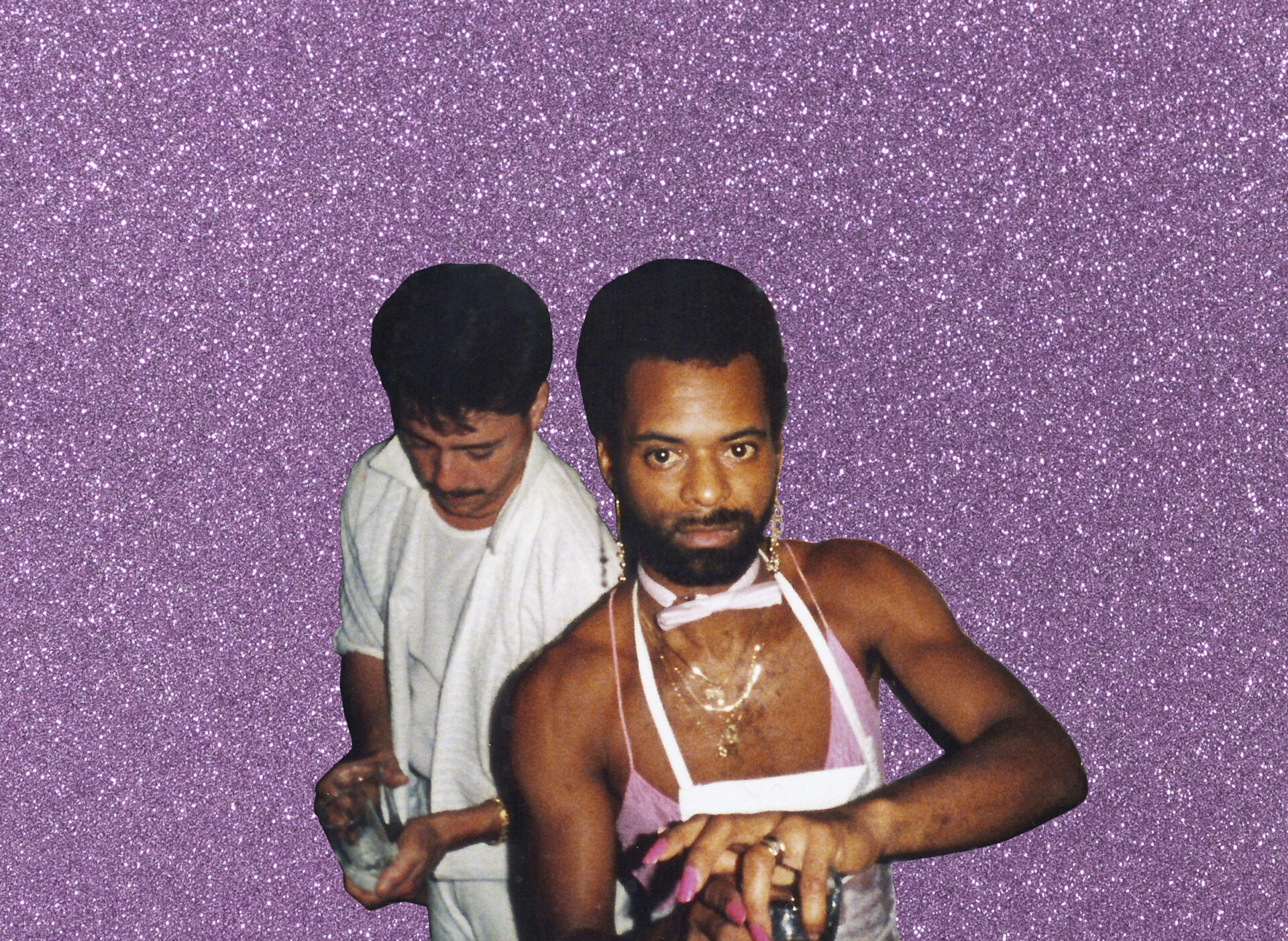

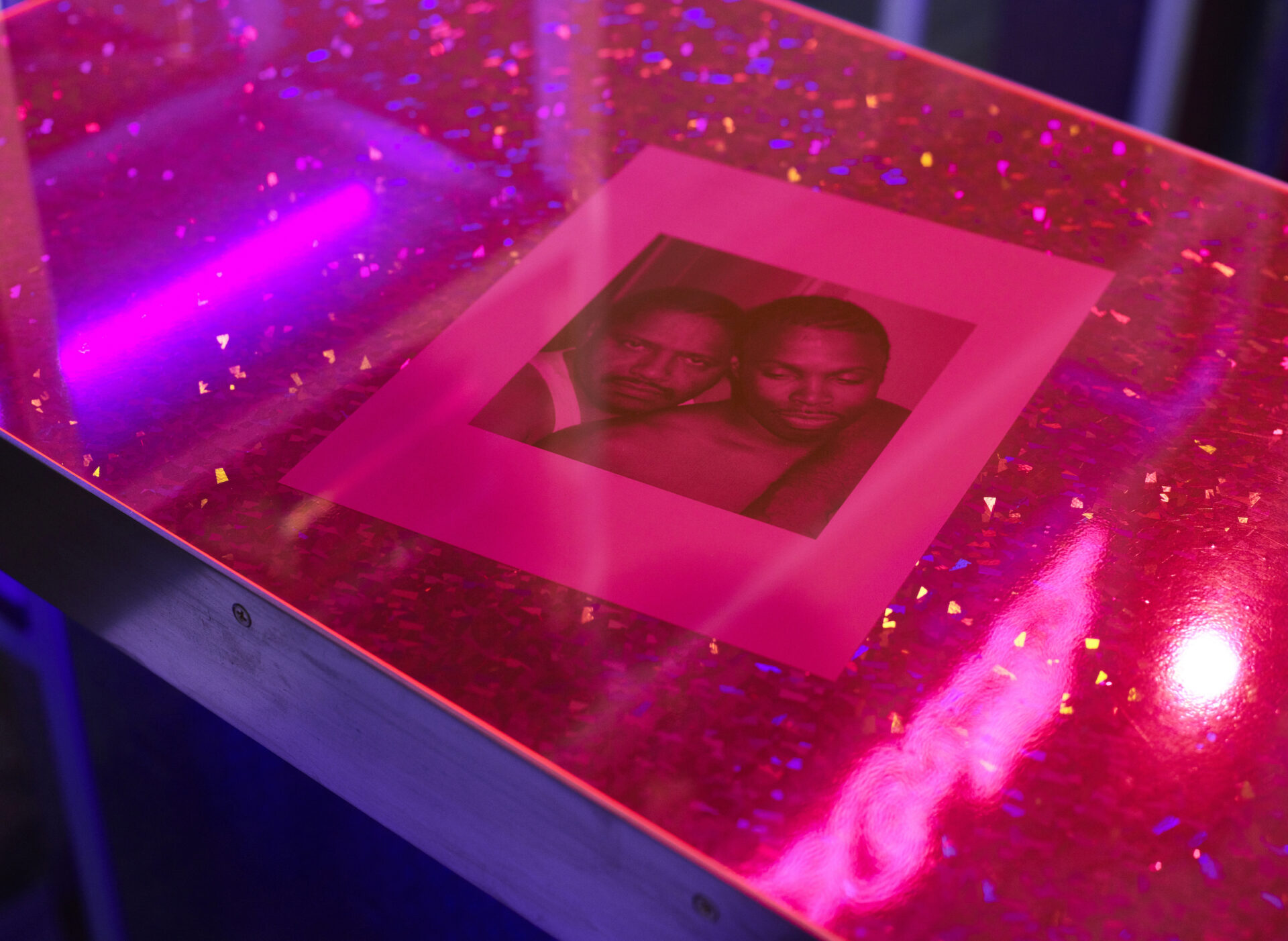

The New Eagle Creek Saloon (2019 — ongoing) is an installation, and a vibe, that reimagines my father’s bar—the first black-owned gay bar in San Francisco. I built the glittering bar structure—glowing somewhere between a monument and an altar—as an invitation, a place to be, and an invocation. I did not want to make a project about the bar; I needed to make a project that was the bar, that bent space and time and reanimated the bones of the Eagle Creek in an intergenerational revival. So, my bar is not quiet as it honors; it is a party. It is all my friends and my dad’s people. It is permission to dance and dream, to call the names of those lost, and to see one another as we are in the glow of our own small moments of freedom.

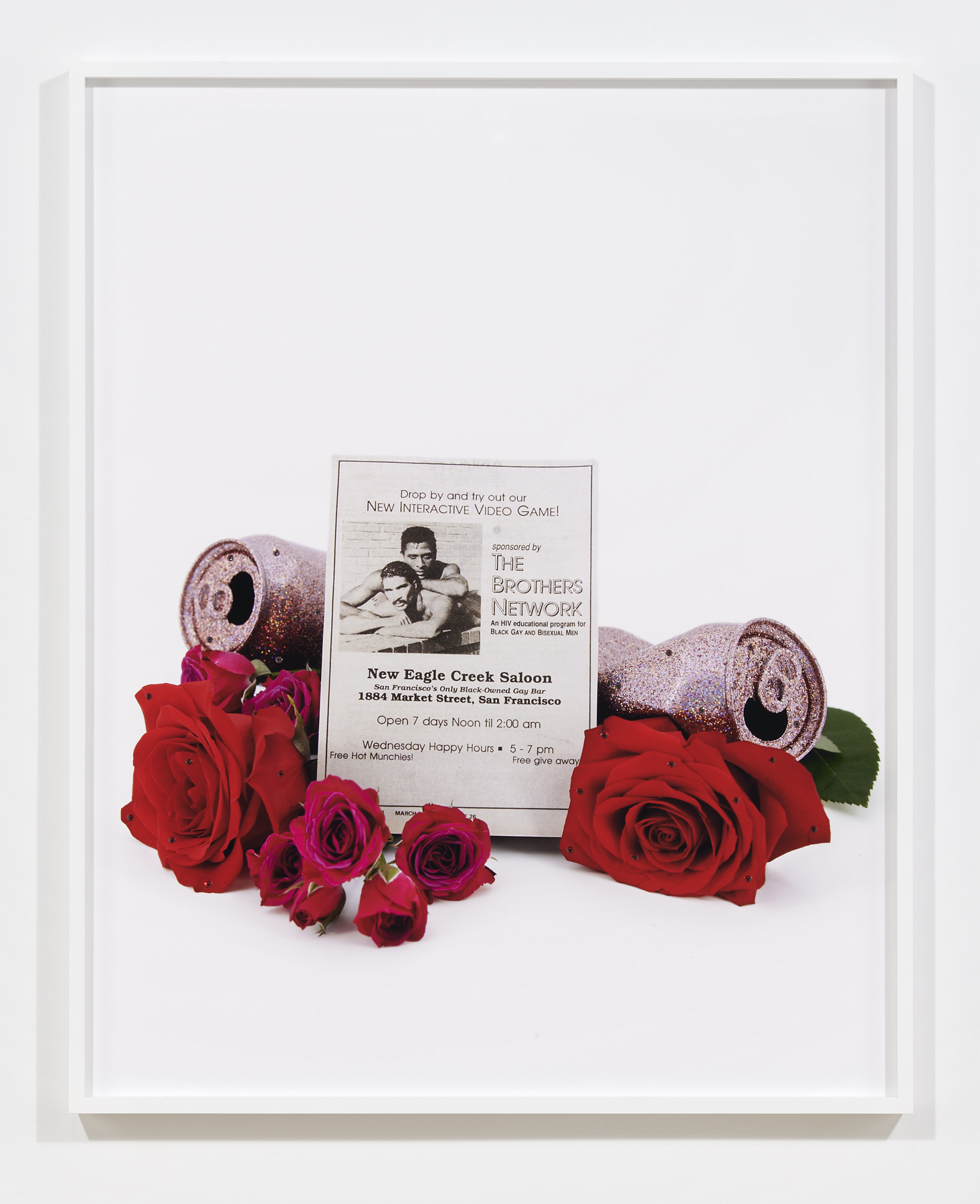

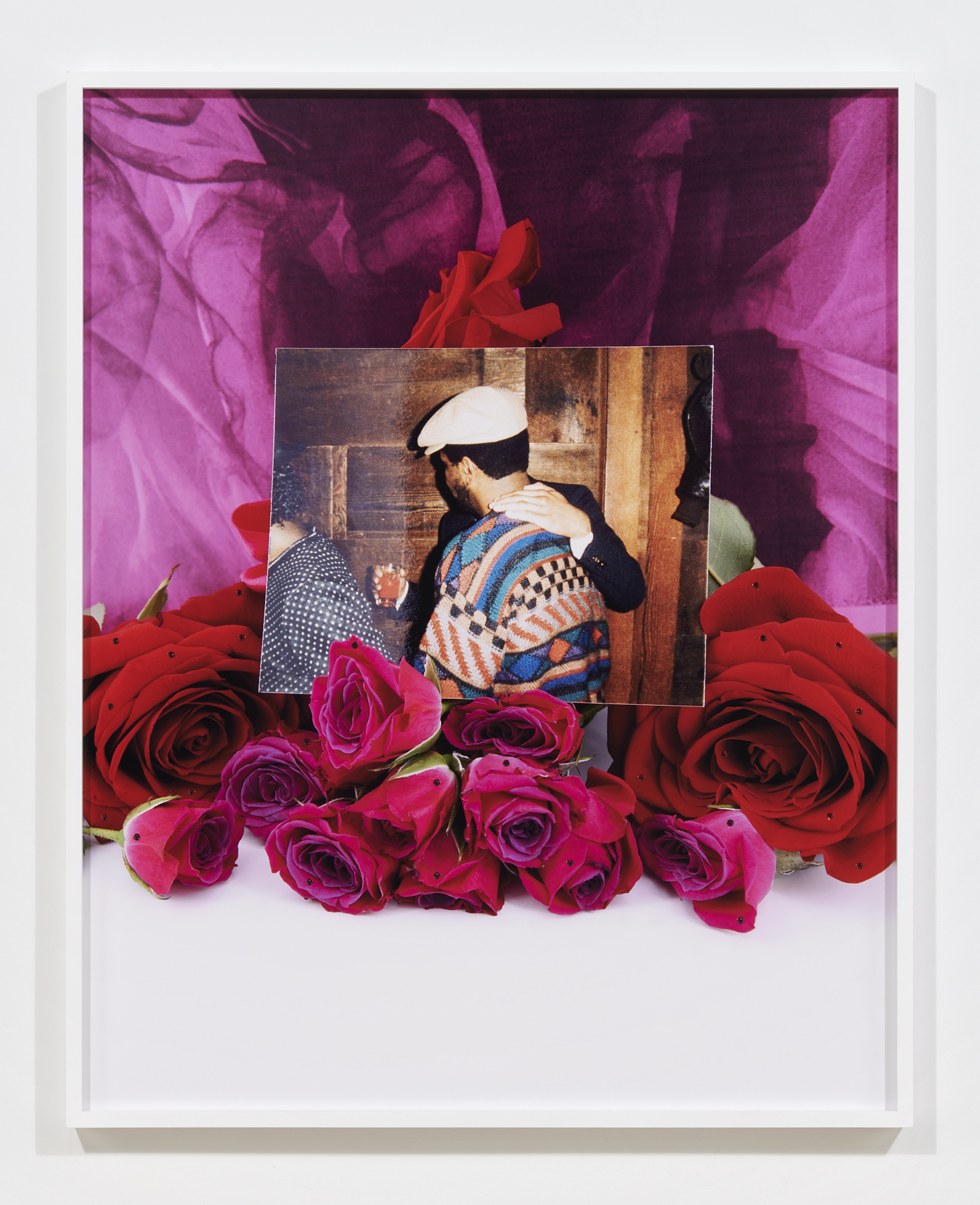

In 1990, Rodney Barnette (aka my dad) opened the New Eagle Creek Saloon to serve a multiracial gay community marginalized by the racist profiling practices of San Francisco’s queer bar scene at that time. My dad’s brothers helped remodel the interior and added a large picture window, and talented patrons added flair to the decor. Located at 1884 Market Street, the bar was a space of celebration and resistance—hosting fundraisers for activist groups,

honoring Black holidays and heroes, and participating in the historic Market Street vigils for those lost to AIDS. Though the bar closed in 1993, its slogan embodies its legacy: “A friendly place, with a funky bass, for every race.”

The project has been hosted by many institutions but operates as its own independent community space, gathering archival materials, making friends and providing new programming as it travels. People are invited to raise a glass at the bar, dance the afternoon away, read a zine featuring ephemera from the original bar, experience film screenings, live music, DJs, panel talks and an ever-expanding range of offerings. I am introducing the New Eagle Creek Saloon into the channels of existing queer histories, but I am also manifesting its own archive, which recognizes the limits of “official histories” and celebrates the unknown and unknowable.

— Sadie Barnette

The New Eagle Creek Saloon (2019 — ongoing) is an installation, and a vibe, that reimagines my father’s bar—the first black-owned gay bar in San Francisco. I built the glittering bar structure—glowing somewhere between a monument and an altar—as an invitation, a place to be, and an invocation. I did not want to make a project about the bar; I needed to make a project that was the bar, that bent space and time and reanimated the bones of the Eagle Creek in an intergenerational revival. So, my bar is not quiet as it honors; it is a party. It is all my friends and my dad’s people. It is permission to dance and dream, to call the names of those lost, and to see one another as we are in the glow of our own small moments of freedom.

In 1990, Rodney Barnette (aka my dad) opened the New Eagle Creek Saloon to serve a multiracial gay community marginalized by the racist profiling practices of San Francisco’s queer bar scene at that time. My dad’s brothers helped remodel the interior and added a large picture window, and talented patrons added flair to the decor. Located at 1884 Market Street, the bar was a space of celebration and resistance—hosting fundraisers for activist groups, honoring Black holidays and heroes, and participating in the historic Market Street vigils for those lost to AIDS. Though the bar closed in 1993, its slogan embodies its legacy: “A friendly place, with a funky bass, for every race.”

The project has been hosted by many institutions but operates as its own independent community space, gathering archival materials, making friends and providing new programming as it travels. People are invited to raise a glass at the bar, dance the afternoon away, read a zine featuring ephemera from the original bar, experience film screenings, live music, DJs, panel talks and an ever-expanding range of offerings. I am introducing the New Eagle Creek Saloon into the channels of existing queer histories, but I am also manifesting its own archive, which recognizes the limits of “official histories” and celebrates the unknown and unknowable.

— Sadie Barnette

The New Eagle Creek Saloon was commissioned by The Lab, San Francisco, with support from the California Arts Council and the San Francisco Arts Commission.

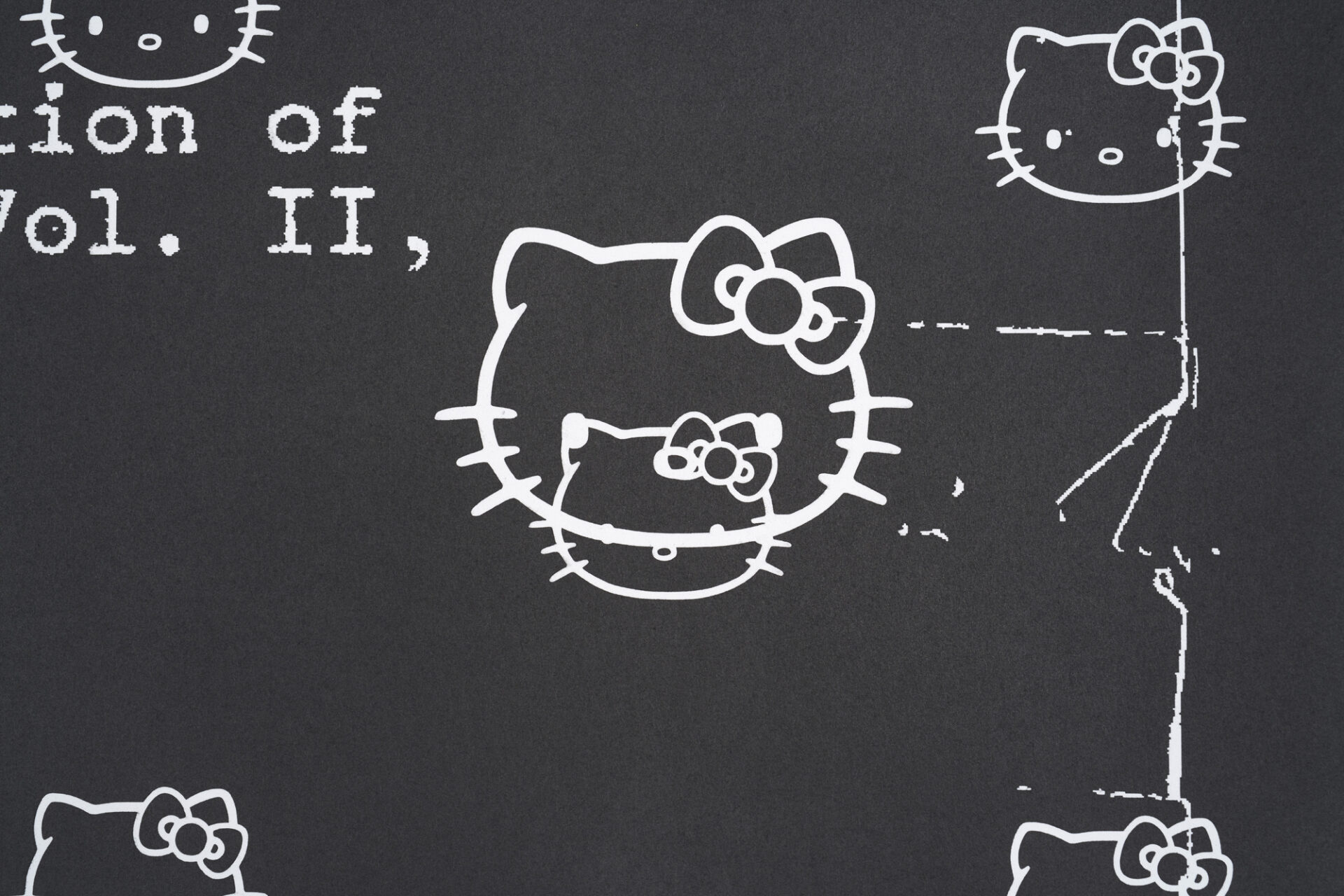

“INHERITANCE” AT JESSICA SILVERMAN (2021)

“Inheritance” is a gift and a responsibility, a birthright and a debt. This exhibition, as with much of my practice, attends to the personal nature of generational legacies to inflect the constant struggle for freedom with urgency, collapsing temporal distinctions of past and present. “Family Tree” is a salon-style self portrait as deconstructed family tree; with drawings like “Cassandra’s Great Great Granddaughter” and “Uncle Rodney’s Daughter,” I am locating myself as a relational member of a continuum.

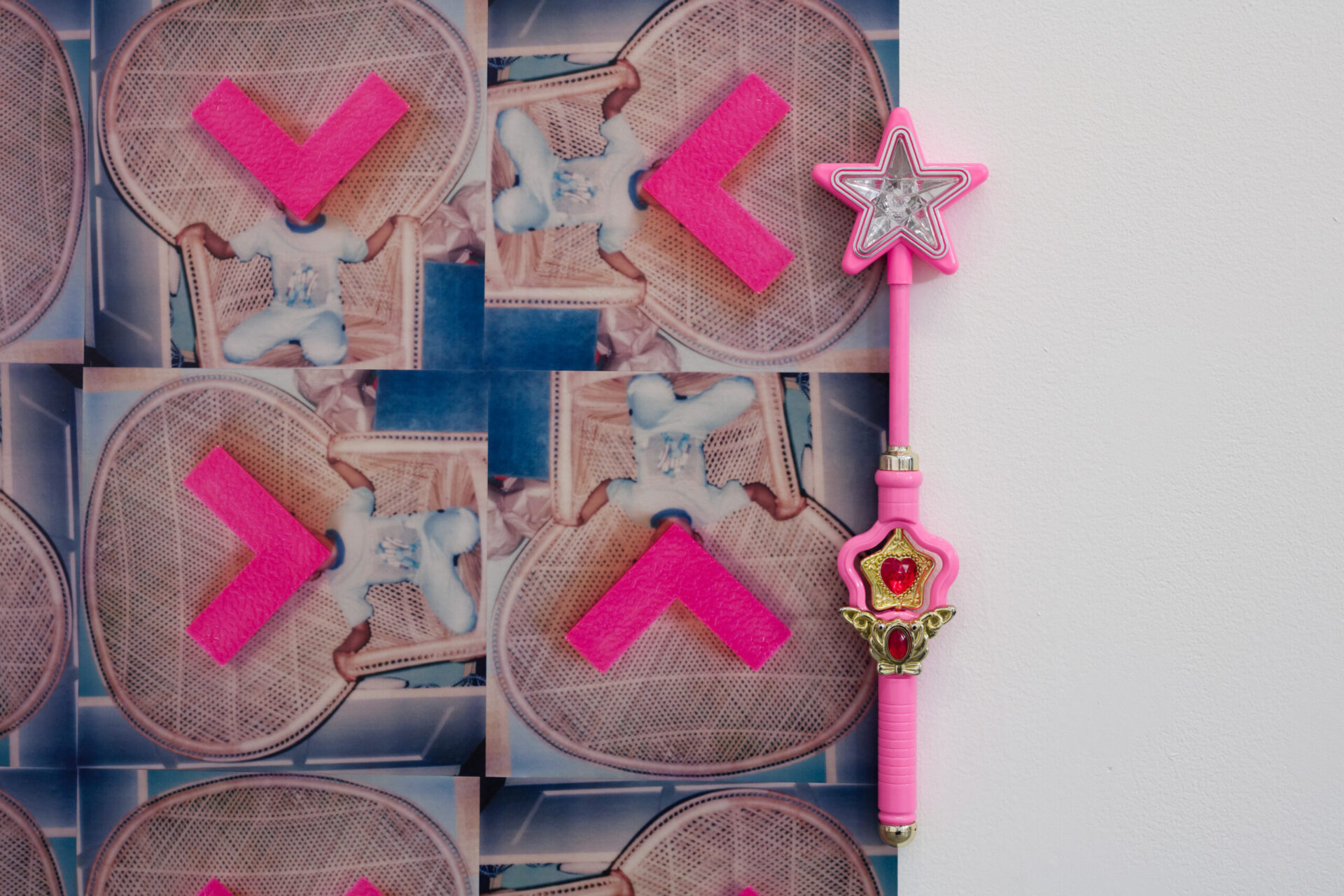

Stacks of glitter speakers, tools for communication and amplification of culture, are painted with automotive metal flake, or “candy paint,” finishes and pay tribute to the car culture of my California upbringing and the generative act of creating something grand and monolithic out of something ordinary. Whether it be rims on a car, rhinestones on a manicure, or flourishes of home decor, these acts of adornment are the ways that we become ourselves, announce ourselves, and find each other. Other everyday objects, such and aluminum cans or vintage couches, receive the same glittering and holographic treatments. With the sculptural works in this “Home Good” series I am literally shining light on the magic within the mundane and holding the living room as common but sacred space.

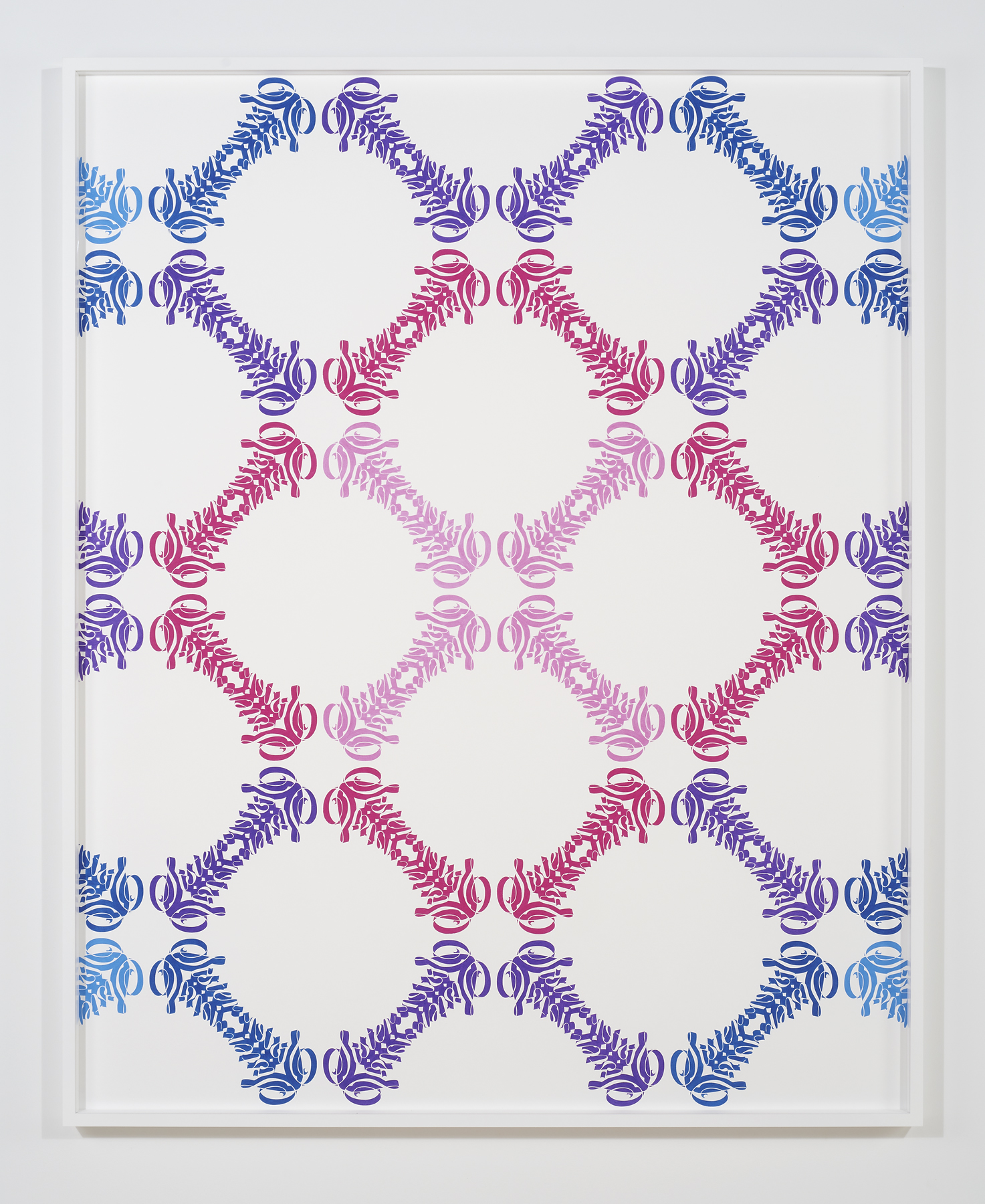

In my “Text Compositions,” I make graphic drawings using only words, sometimes bold and simple and sometimes detailed and intricate. These works try to fit the biggest concepts into the smallest amount of information — an elegant economy for the grand and overwhelming Everythingness of our social structures and resulting human experiences. They point to, walk around, dance with, ideas too big for language.

I make this work even when I don’t think I can. I make this work by leaning back on those that came before me and drawing their breath through my lungs, puffing my chest out, pretending I can. I make this work even though it feels like the end of the world. Because I think this might also be what the beginning feels like. A glittering rage, a head full of history but still laughing and working and bothering to paint my nails, to show up, to show out, to embody.

—Sadie Barnette

“Inheritance” is a gift and a responsibility, a birthright and a debt. This exhibition, as with much of my practice, attends to the personal nature of generational legacies to inflect the constant struggle for freedom with urgency, collapsing temporal distinctions of past and present. “Family Tree” is a salon-style self portrait as deconstructed family tree; with drawings like “Cassandra’s Great Great Granddaughter” and “Uncle Rodney’s Daughter,” I am locating myself as a relational member of a continuum.

Stacks of glitter speakers, tools for communication and amplification of culture, are painted with automotive metal flake, or “candy paint,” finishes and pay tribute to the car culture of my California upbringing and the generative act of creating something grand and monolithic out of something ordinary. Whether it be rims on a car, rhinestones on a manicure, or flourishes of home decor, these acts of adornment are the ways that we become ourselves, announce ourselves, and find each other. Other everyday objects, such and aluminum cans or vintage couches, receive the same glittering and holographic treatments. With the sculptural works in this “Home Good” series I am literally shining light on the magic within the mundane and holding the living room as common but sacred space.

In my “Text Compositions,” I make graphic drawings using only words, sometimes bold and simple and sometimes detailed and intricate. These works try to fit the biggest concepts into the smallest amount of information — an elegant economy for the grand and overwhelming Everythingness of our social structures and resulting human experiences. They point to, walk around, dance with, ideas too big for language.

I make this work even when I don’t think I can. I make this work by leaning back on those that came before me and drawing their breath through my lungs, puffing my chest out, pretending I can. I make this work even though it feels like the end of the world. Because I think this might also be what the beginning feels like. A glittering rage, a head full of history but still laughing and working and bothering to paint my nails, to show up, to show out, to embody.

—Sadie Barnette

“Inheritance,” a solo exhibition at Jessica Silverman, San Francisco, November 2021 — January 2022

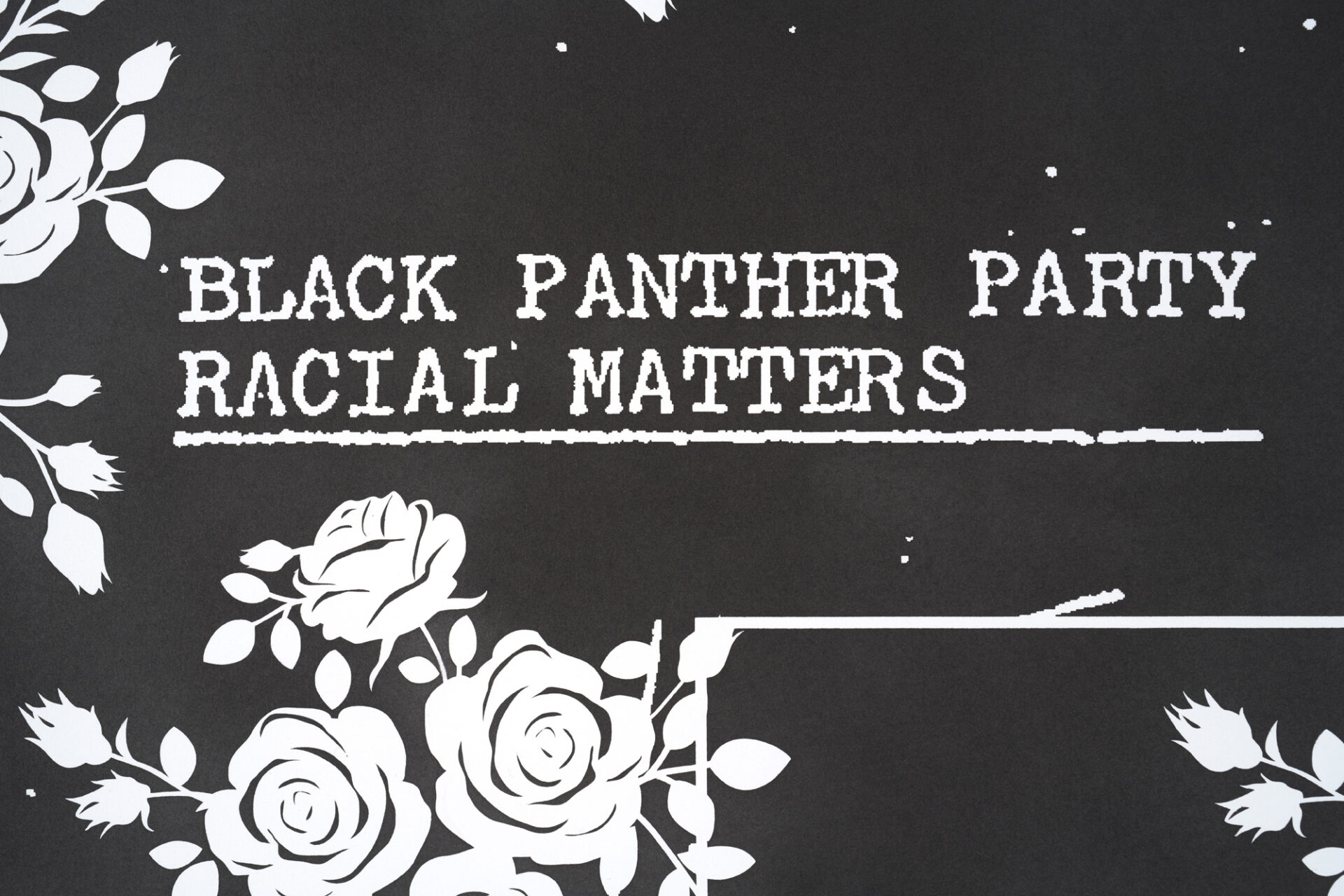

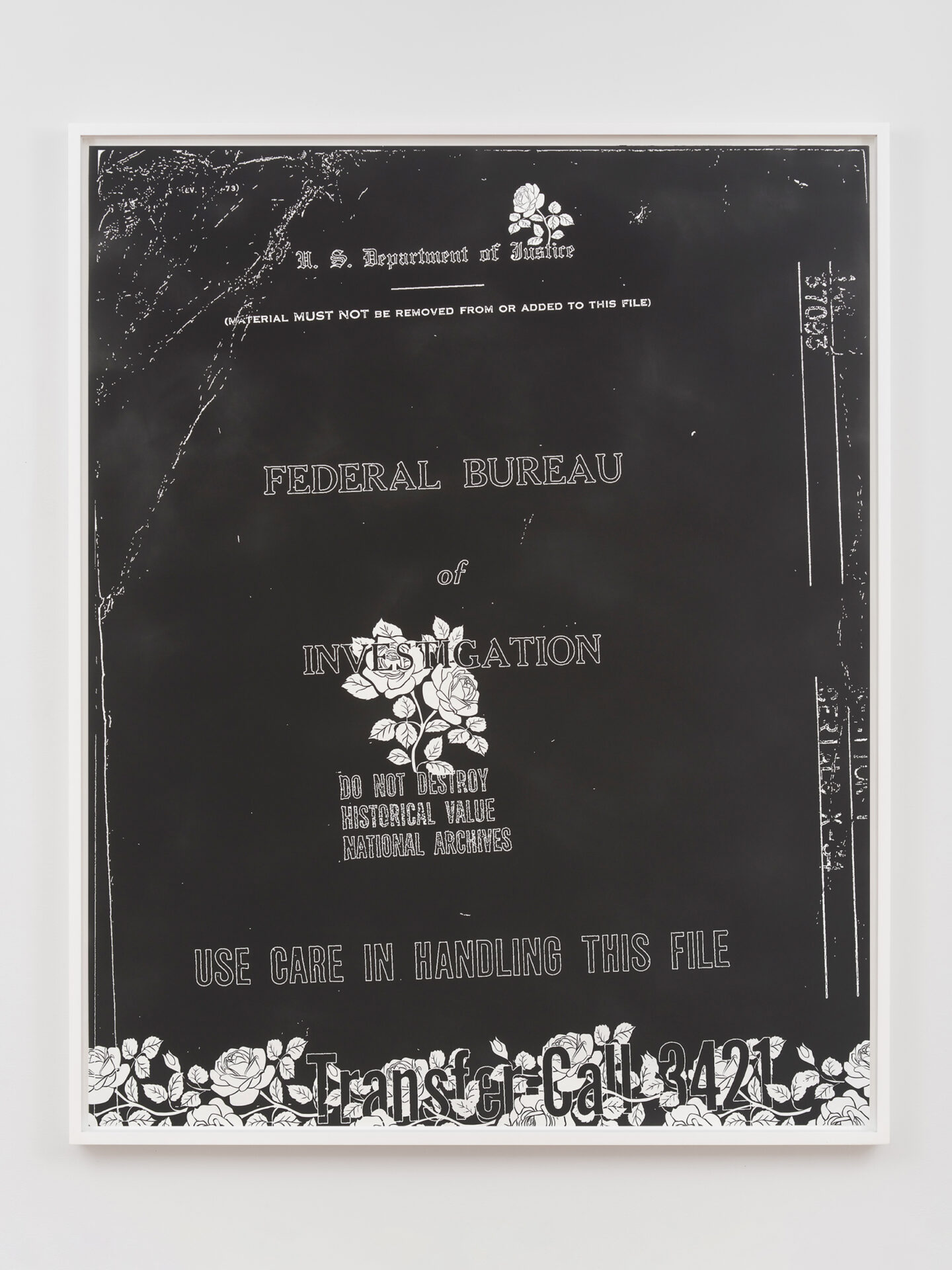

THE FBI PROJECT (2016-ONGOING)

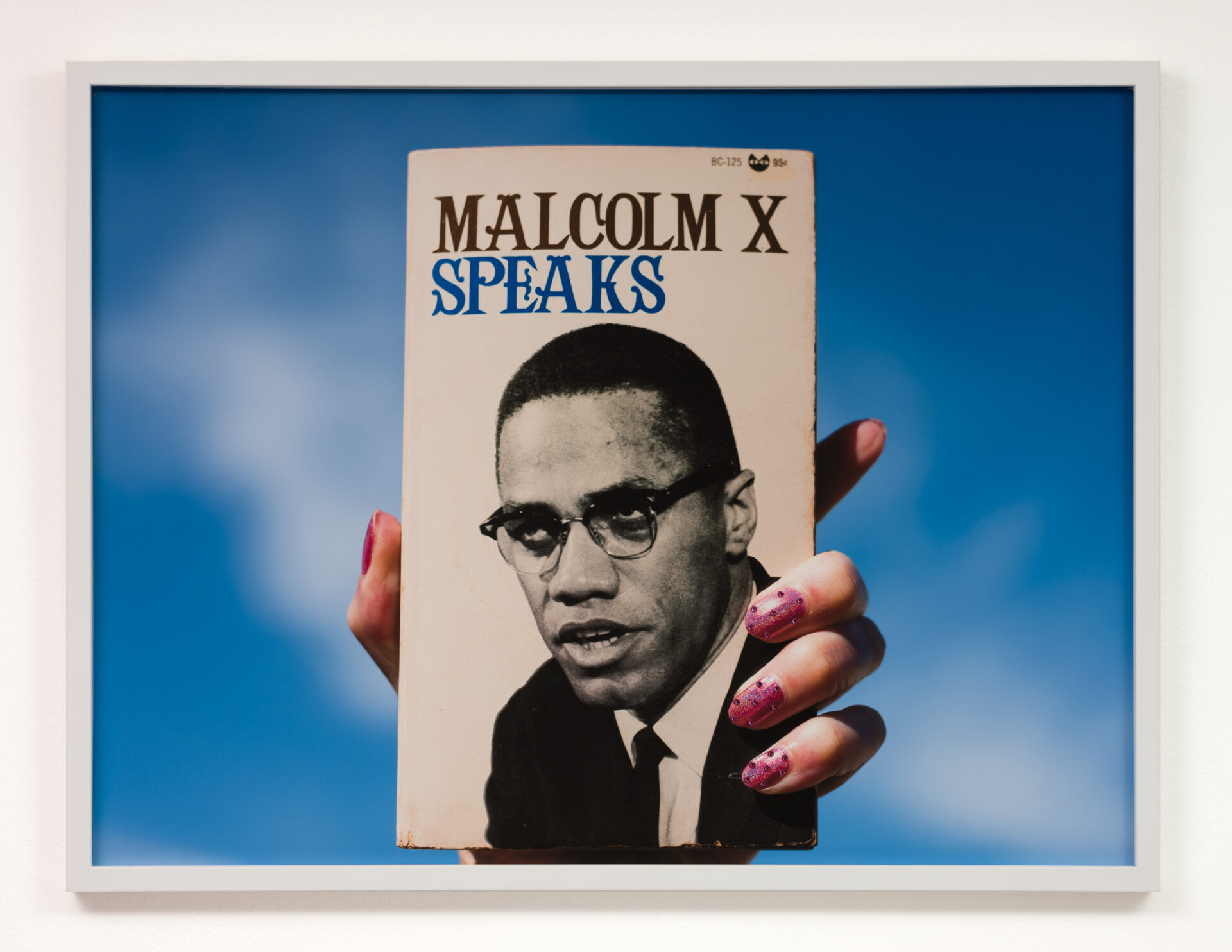

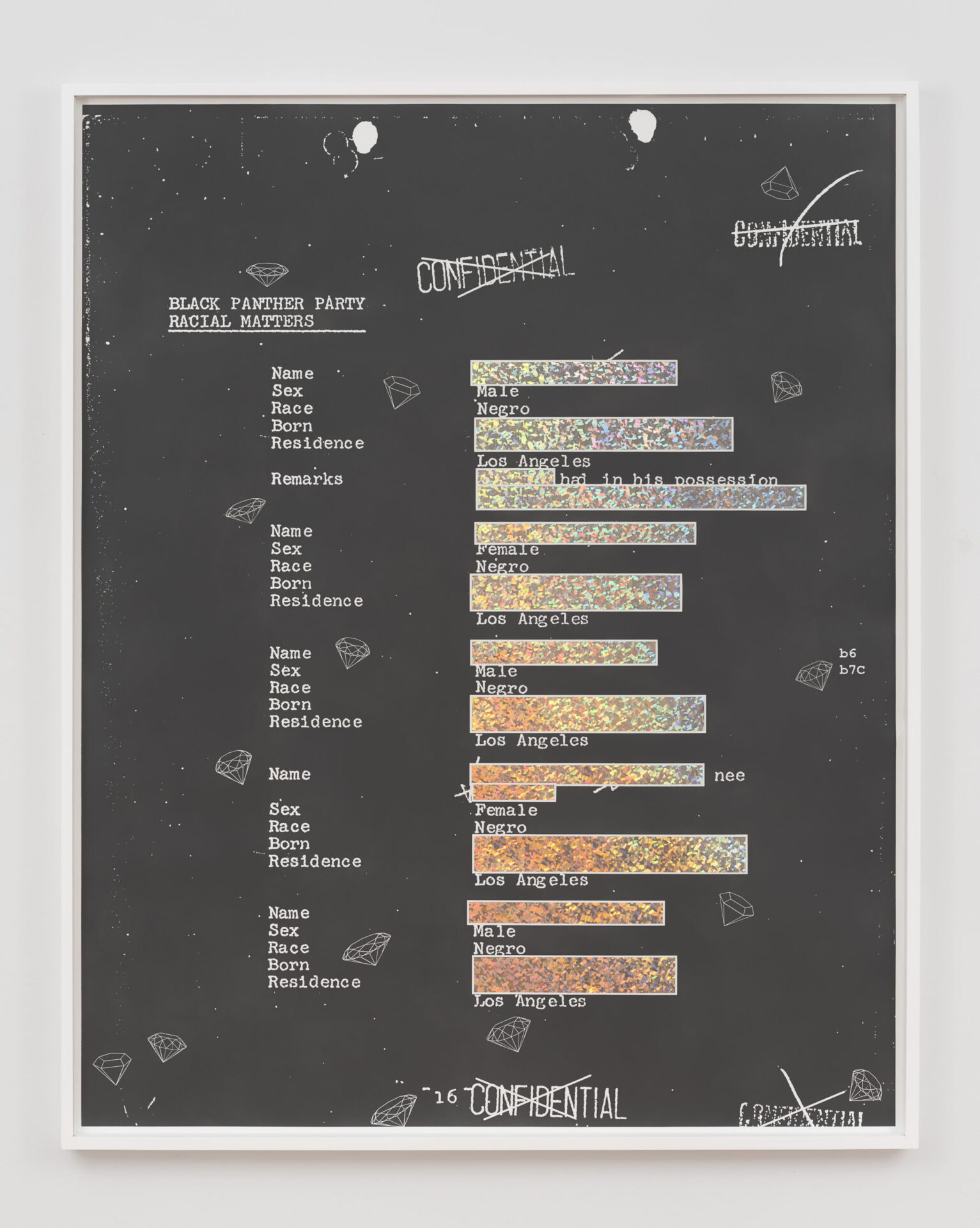

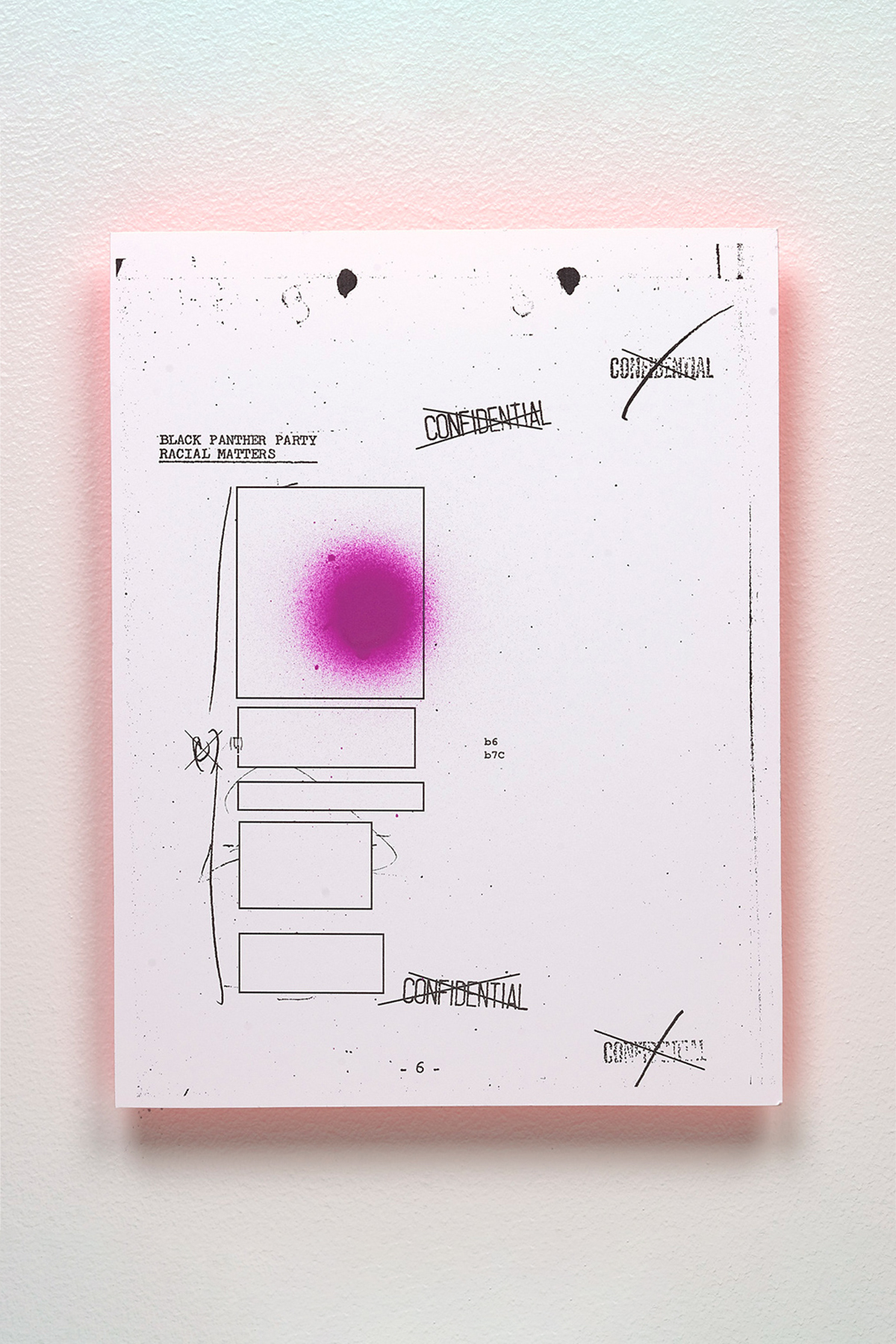

The FBI Project (2016 — ongoing) employs a variety of material interventions engaging the FBI’s 500-page surveillance file amassed on my father, Rodney Barnette, during his time organizing with the Black Panther Party and helping Angela Davis in her fight for exoneration. Through a Freedom of Information Act request, and after four years of back-and-forth with the FBI, my family obtained this chilling dossier that details the routine surveillance of my father by special agents, harassment and intimidation of family and friends, and the solicitation of informants to infiltrate the Black Power Movement. Combing through page after page of state-sanctioned attempts to discredit, frame, to destroy and undo my father, I thought, “Damn, I’m lucky he is alive. That he lived to tell. That I was born.” My second thought was, “Make this art, make this do something.” Trusting in my rigorous yet playful aesthetic of minimalism, restraint, and color, I started making collages and drawings that appropriated the official documents. I wanted to reclaim them and make them live in my world.

I started in 2016 at document scale. I took the 8.5-by-11-inch FBI pages, which were heavily redacted and punctuated with officious markings and handwritten margin notes, and splashed them with bright pink spray paint and pastel rhinestones. The spray paint points to graffiti and “tagging” (an act of reclamation), to my own lexicon of redactions and the unknowable.

The crystal adornment is an impossible and tiny act of healing. I also figured pink glitter would be a kind of kryptonite to J. Edgar Hoover’s tortured ghost.

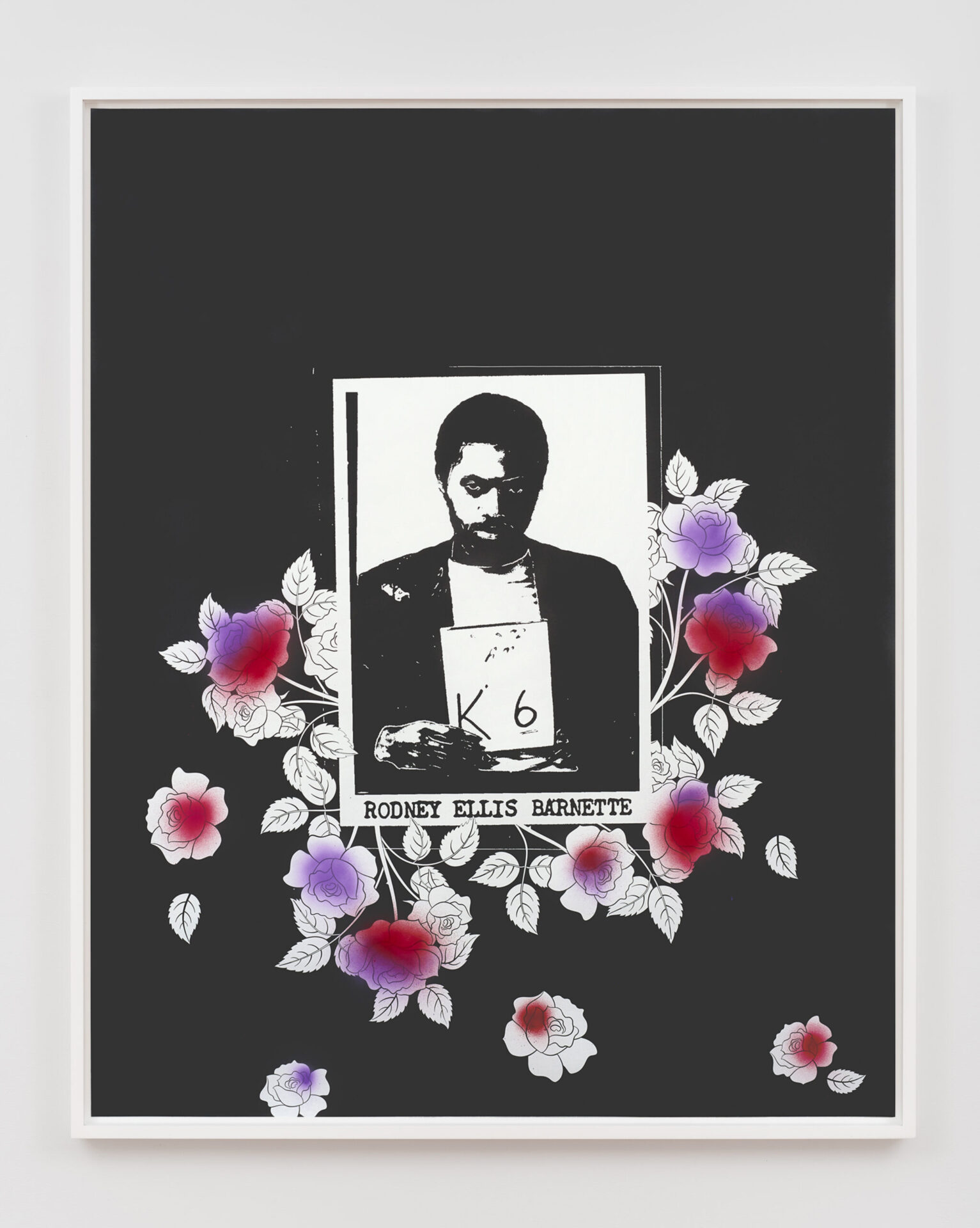

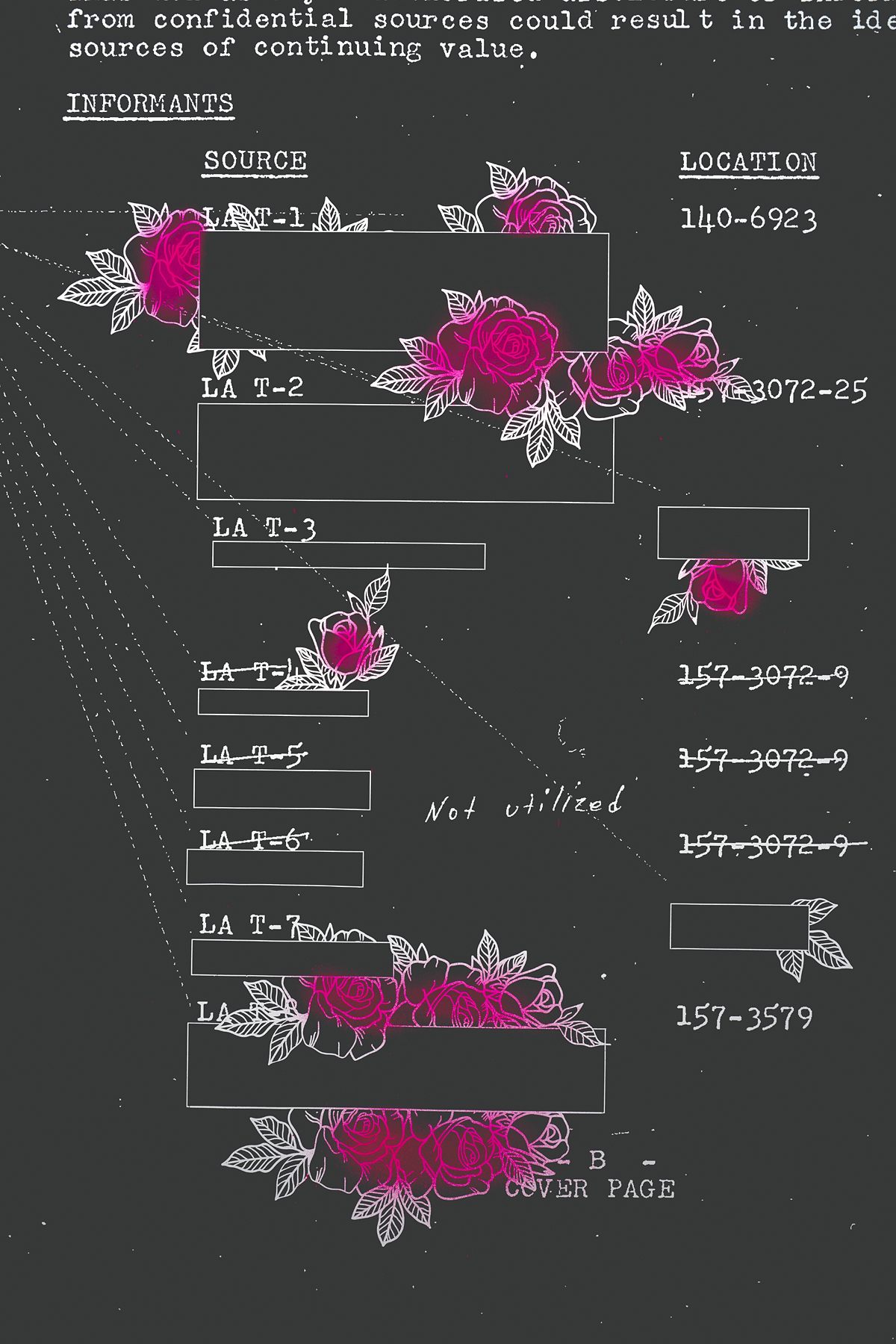

In 2020, I started the series “FBI Drawings,” steering the work toward a shift in scale and materiality that holds weight and claims more space, underscoring that this project is one of redress. In these large-scale (5 x 4 ft) drawings, the file pages are tonally inverted, suggesting further transmutation from the original authority and intent, and rendered by hand in a heavy application of powdered graphite on stark white paper. The slowed-down, labor-intensive act of making these pages into drawings affords me time to meditate on the bravery, the politic, the real life people, sisters, fathers. . . this new hand-drawn copy becomes more real than the original. I add flowers (roses specifically) to the bureaucratic documents to honor, to mourn and memorialize, to add life, and to suggest evidence of the domestic and rituals of care. In other works, I collage holographic vinyl into the rectangular voids of redactions to propose a counter-surveillance, a resistance, and a restorative technology.

— Sadie Barnette

The FBI Project (2016 — ongoing) employs a variety of material interventions engaging the FBI’s 500-page surveillance file amassed on my father, Rodney Barnette, during his time organizing with the Black Panther Party and helping Angela Davis in her fight for exoneration. Through a Freedom of Information Act request, and after four years of back-and-forth with the FBI, my family obtained this chilling dossier that details the routine surveillance of my father by special agents, harassment and intimidation of family and friends, and the solicitation of informants to infiltrate the Black Power Movement. Combing through page after page of state-sanctioned attempts to discredit, frame, to destroy and undo my father, I thought, “Damn, I’m lucky he is alive. That he lived to tell. That I was born.” My second thought was, “Make this art, make this do something.” Trusting in my rigorous yet playful aesthetic of minimalism, restraint, and color, I started making collages and drawings that appropriated the official documents. I wanted to reclaim them and make them live in my world.

I started in 2016 at document scale. I took the 8.5-by-11-inch FBI pages, which were heavily redacted and punctuated with officious markings and handwritten margin notes, and splashed them with bright pink spray paint and pastel rhinestones. The spray paint points to graffiti and “tagging” (an act of reclamation), to my own lexicon of redactions and the unknowable. The crystal adornment is an impossible and tiny act of healing. I also figured pink glitter would be a kind of kryptonite to J. Edgar Hoover’s tortured ghost.

In 2020, I started the series “FBI Drawings,” steering the work toward a shift in scale and materiality that holds weight and claims more space, underscoring that this project is one of redress. In these large-scale (5 x 4 ft) drawings, the file pages are tonally inverted, suggesting further transmutation from the original authority and intent, and rendered by hand in a heavy application of powdered graphite on stark white paper. The slowed-down, labor-intensive act of making these pages into drawings affords me time to meditate on the bravery, the politic, the real life people, sisters, fathers. . . this new hand-drawn copy becomes more real than the original. I add flowers (roses specifically) to the bureaucratic documents to honor, to mourn and memorialize, to add life, and to suggest evidence of the domestic and rituals of care. In other works, I collage holographic vinyl into the rectangular voids of redactions to propose a counter-surveillance, a resistance, and a restorative technology.

— Sadie Barnette